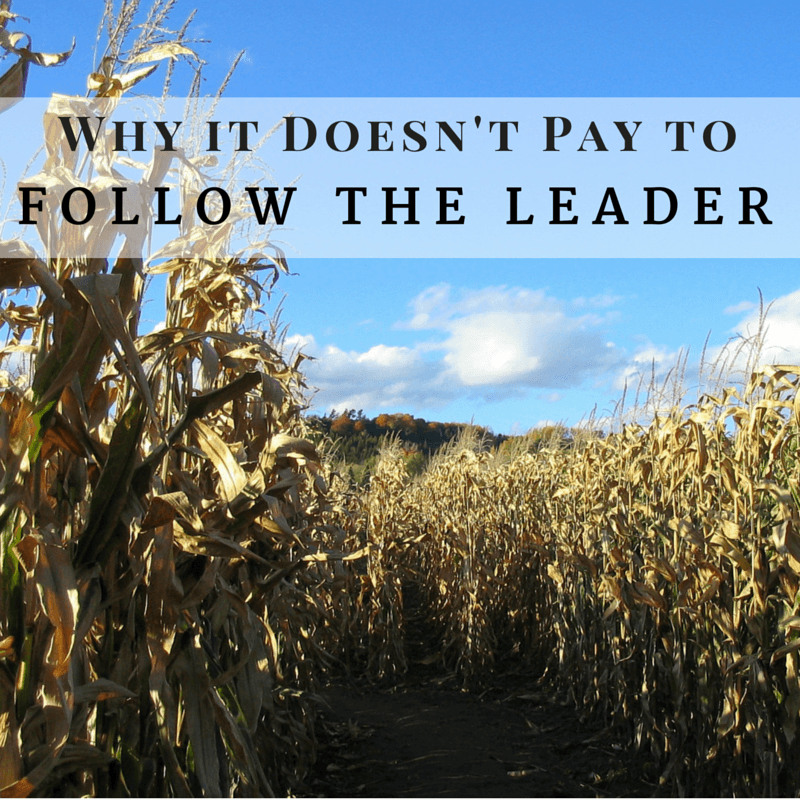

It’s fall in New England, and there are certain activities that are a must-do before the season is over.

There is funnel cake at the fair, apple picking, and a warm apple cider donut or two. The sights and smells of fall are not limited to leaf peeping, though that’s certainly on the list as well.

One of the other treats I’ve come to enjoy, that I hadn’t experienced before moving here, is a good corn maze. More and more farms are carving elaborate paths through their corn, with clues to help children young and old find their way.

A few weeks ago, a friend and I decided to tackle a three-part maze at Coppal House Farm in Lee, NH.

During the course of our journey, I couldn’t help but notice how we worked together and how it changed as the day went on.

Getting started

My friend and I just recently started hanging out away from work. We’ve known each other for a while, but this was new territory.

Our budding friendship was obvious in how we got started. Each of us wanted to engage the other in decision making. At least at first.

We were prompted with questions about honey bees and tried to determine who had the best answer. As we progressed, so did the debates. Neither of us knew the answers for sure, so each of us picked a side and played devil’s advocate to reason them out.

Getting lost

After a while, I noticed that when I suggested a question or direction, my friend was happy to follow. Later, when I asked why, she indicated that she had idea, so she might as well follow me. From her view, I seemed to know what I was doing.

At one point, I got us hopelessly lost and we had to backtrack. Clearly I didn’t know what I was doing, yet she still followed.

Eventually, we ran into a few small families. Rather than take away from the childrens’ ability to guess the answers and directions, we just started walking. For the most part, I led the way, asking for help to find areas where we might be looping back on our path.

Getting through

Along the way, we laughed at our game of follow the leader. I pointed out that I had no better ideas than anyone else where to go, but experience told me we’d get out if we kept moving in the direction of the exit. If not, we’d be able to back track and find our way.

From my friend’s perspective, she was just happy to hang out. It wasn’t a puzzle to solve, but rather a fun way to spend an hour or two. She had no certainty in her direction, and was fine with me taking responsibility for us finding our way.

We discussed the correlation of our maze travels to our experience at work. How often do we follow the leader, assuming he or she has answers we don’t? Many times, being a leader means being the one willing to take risks. To be the first to step out on the journey and carve a path.

Others following may be a surprise – after all, we aren’t positive where we’re going. However, there is less perceived risk in following others than being the one to take the lead.

Making wrong turns and getting lost is inevitable. Leaders don’t quit when they run into these situations, they expect them. They know they don’t have a map, look for signs of something familiar, and work through the unknowns when they don’t find them.

Getting experience

It is the experience of getting lost, and finding our way through, that builds confidence in our abilities to reason through the unknown.

In most of our lives and work, there is no map. If someone else has gone before, there may be landmarks and instructions we can follow. Often, however, we run into forks in the road. New conditions. Choices we can make. Which way do we go?

By picking a path and moving forward, we are building our confidence. We learn patterns and odds. We may run into a dead end and have to backtrack. Changing course becomes part of our process. Risk starts to become routine.

If we follow others, we learn how to follow. When we take the lead, we learn what works and what doesn’t. We build our leadership ability with every decision, including every wrong turn. We may be winging it, but we become experienced wingers.

The pivot point is the first time we get really lost. It’s uncomfortable to get lost. To make mistakes. To venture into the unknown without a map. So some will stop the first time they get lost. From there, they will follow others. From there, they become really good at following.

To become and stay a leader, to build resilience, we have to keep going. We have to be willing to get lost. We have to have confidence in our ability to find our way through, even if we’re not sure where we’re headed.

Getting balance

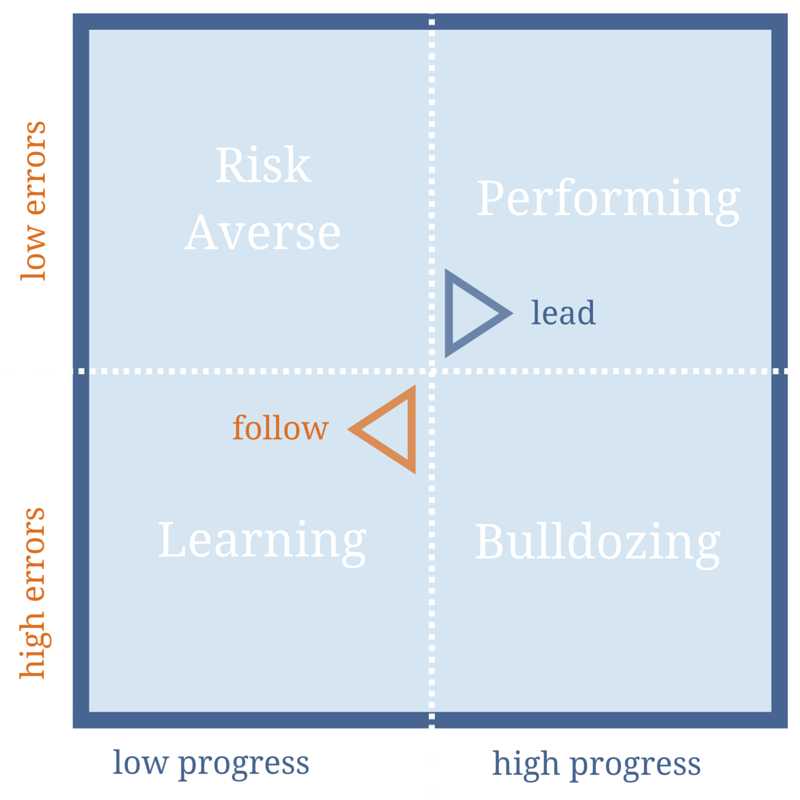

In work and life, we learn from our experiences. We find what works and what doesn’t. Over time, if we apply our learnings, we make fewer mistakes and more progress.

Effective leaders balance forward progress against the risk of making errors. If there are a lot of mistakes in the name or progress, we may be bulldozing others just to move ahead. On the other hand, if there are very few errors, with little forward momentum, it may mean a risk aversion that prevents the necessary learning to get past mistakes to progress.

The ultimate goal of a leader is to move from learner – defined by a fits and starts of progress, with mistakes made along the way – to a performer.

[Tweet “Leadership is a balance of progress and errors. Learning is the ingredient that tips the scales.”]

WARNING

Regardless of whether we are a leader ourselves, sometimes we must follow others. We can play both roles, depending on the situation. However, when we are following, it’s good to remember that our leaders rarely have a map. Sometimes, they have no better idea than we do which way to go.

Our leaders can get us lost. They can lead us in circles or to dead ends that we have to back out of. If we’re not careful, we can follow a bulldozer right off a cliff.

Rather than blindly follow the leader, we must consider what our eyes – and sometimes our gut – are telling us. Maybe we’ve seen similar signs or landmarks in the past. We can rely on our own experience and speak up if we think we’re headed in the wrong direction.

When we are the ones leading, and those following speak up, it pays to listen. While our experience may tell us we’ll figure things out, they may have insights we lack. We will eventually get out, but we may be able to save our time and resources by listening to alternatives.

Team building

Sending a group into a maze will reveal a lot about their natures and team dynamics. Who naturally leads? Who breaks off if he or she isn’t listened to? Who quietly follows the group? Who questions the leader?

While corn mazes have proven to be a fun New England tradition, they are also a great opportunity to learn about ourselves, our relationships with others, and maybe even push ourselves past the pivot point.

Do you have other ideas on how to build experience leading without a map? Please share your thoughts in the comments. I’d love to hear from you.